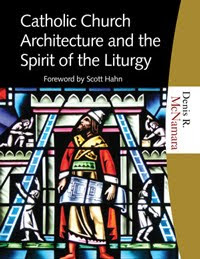

As you know, we are very excited about the new book from CMR contributor Denis McNamara. For those of you who don’t know, Denis (DMac) is Assistant Director and Faculty Member at The Liturgical Institute located at Mundelein Seminary in the Archdiocese of Chicago. Denis has a B.A. in History of Art from Yale University and an M.Arch.H. and Ph.D. in Architectural History from the University of Virginia. His new book “Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy” will be released in very early November.

As you know, we are very excited about the new book from CMR contributor Denis McNamara. For those of you who don’t know, Denis (DMac) is Assistant Director and Faculty Member at The Liturgical Institute located at Mundelein Seminary in the Archdiocese of Chicago. Denis has a B.A. in History of Art from Yale University and an M.Arch.H. and Ph.D. in Architectural History from the University of Virginia. His new book “Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy” will be released in very early November.

It is with great pleasure that we can present for the first time, the foreword to the book written by none other than Dr. Scott Hahn.

After the exodus from Egypt, as Israel sojourned in the desert, God gave Moses “the pattern of the tabernacle and of all its furniture” (Exodus 25:9). And so Moses commanded the construction of this portable sanctuary of God’s presence among his chosen people. Centuries later, in Jerusalem, God gave David “the plan of the vestibule of the temple, and of its houses, its treasuries, its upper rooms, and its inner chambers, and of the room for the mercy seat” (1 Chronicles 28:11). To the son of David, King Solomon, God also gave the right to call his temple “the house of the Lord” and “the house of God” (1 Chronicles 28:20 – 21).

The early Christians saw both the tabernacle and the temple as biblical “types” foreshadowing the Christian Church. They were earthly sanctuaries that would find their fulfillment in the worship of heaven and earth that we find detailed in the New Testament books of Hebrews and Revelation (see Hebrews 8 –10 and Revelation 11:19). The Church at worship included what Catholics traditionally call the Church Militant, the Church Triumphant, and the Church Suffering — the great cloud of witnesses — the communion of the Church on earth, in heaven, and in purgatory.

But most of this was invisible to the eye. It was made known, however, through the preaching of the Church fathers, especially those we know as “mystagogues”: Ambrose, Cyril of Jerusalem, John Chrysostom, Augustine, Denis the Areopagite, and Maximus the Confessor.

Mystagogy is guidance in the “mysteries,” in things hidden since the foundation of the world. The mystagogue guided his congregation, especially the new converts, through the external, material appearances to grasp the unseen reality that is interior, spiritual, hidden, and divine. Thus he could demonstrate that the liturgical and sacramental signs have been foreshadowed in both the Old and New Testaments. He could trace their development from shadow (in the Old) to image (in the New) to reality (in heaven).

Ancient mystagogy was intensely concerned not only with rite and gesture, but with architecture as well. What the tabernacle had been to the Israelites, what the temple had been to the Jews, the church was now for the Christians. The Apostolic Constitutions (fourth century) includes a lovely symbolic interpretation of the church building as a ship sailing heavenward. It instructs the bishop thus:

When you call an assembly of the Church as one that is the commander of a great ship, appoint the assemblies to be made with all possible skill, charging the deacons as mariners to prepare places for the brethren as for passengers, with all due care and decency. And first, let the building be long, with its head to the east, with its vestries on both sides at the east end, and so it will be like a ship. In the middle let the bishop’s throne be placed, and on each side of him let the presbytery sit down; and let the deacons stand near at hand, in close and small girt garments, for they are like the mariners and managers of the ship: with regard to these, let the laity sit on the other side, with all quietness and good order. 1

The redactors obviously believed they could trace the pedigree of such ideas back to the apostles themselves.

But somehow these ideas got lost in the shuffle of the ages — so utterly lost that, in our own age, the popes have issued urgent calls for their recovery. In his apostolic exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis (SCar.), Pope Benedict XVI pleads for a “mystagogical catechesis . . . concerned with presenting the meaning of the signs.” He continues: “This is particularly important in a highly technological age like our own, which risks losing the ability to appreciate signs and symbols. More than simply conveying information, a mystagogical catechesis should be capable of making the faithful more sensitive to the language of signs” (SCar., 64). Elsewhere in the same letter, he — like his “apostolic” forebears — emphasizes that mystagogy must include the elements of iconography and architecture:

The profound connection between beauty and the liturgy should make us attentive to every work of art placed at the service of the celebration. Certainly an important element of sacred art is church architecture, which should highlight the unity of the furnishings of the sanctuary. Here it is important to remember that the purpose of sacred architecture is to offer the Church a fitting space for the celebration of the mysteries.” (SCar., 41)

I believe that this book by Denis McNamara is the kind of mystagogy Pope Benedict called for. I believe it is the kind of mystagogy the ancient Church fathers would wish for their own churches. Dr. McNamara knows that to contemplate sacred space is not merely to trace influences in an evolutionary diagram back to Vitruvius. To understand a church requires more than a genealogy of tourist postcards. It requires an interior life. It requires a hope of heaven. It requires a revelation. It calls for mystagogy. All of this is evident in the pages of this book.

Dr. McNamara has given us something we desperately need, something rare and great: at once an achievement of scholarship, a work of mystagogy, and an act of piety.

Professor of Theology and Scripture

Franciscan University of Steubenville

Founder and Director, Saint Paul

Center for Biblical Theology

1. Apostolic Constitutions, 2.57.

Leave a Reply